Penned in 1940, with most of World War II still ahead, Maschwitz & Sherwin’s A Nightingale Sang In Berkeley Square became an overnight sensation. Through Vera Lynn, one of WWII’s most noted entertainers, it offered a little hope to the Allies in dark days.

Vera Lynn Sings “Nightingale” And, somehow, Nightingale became a jazz standard — a part of the repertoire that, love it or hate it, an aspiring jazz musician simply has to know.

To my ears, Nightingale sounds cheesy and culturally outdated. Which of course means it’s due for a harmonic retrofit. In this article, I’ll focus on reharmonizing eight bars of the piece: the first two bars (“that certain night, the night we met”); bars five and six (“there were angels dining at the ritz”); and the initial four bars of the bridge (“the moon that lingered”).

As we’ll see, spending time coloring up just those eight bars makes the piece sound a lot more modern — and palatable!

That Certain Night

Before we get going, it’s probably a good idea to familiarize yourself with the tune. Check out the recording — one of the earliest — above, and then look at the lead sheet to get comfortable with the changes:

Lead Sheet For “Nightingale”

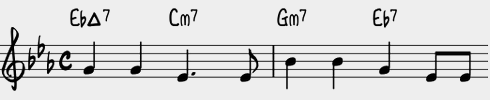

Nightingale starts with a simple progression of Imaj - VImin - IIImin with

the last chord in the progression, an Eb7, treated as a V7 in the key of

Abmaj:

The first three changes, especially, cry out for more interesting harmonic motion. A simple technique to add color is to use chromatic approaches. A chromatic approach is a passing chord that lies a half-step above or below the destination chord. Typically, chromatic approaches are dominant seventh chords, but in some situations it is possible to use very different colors to achieve the same sense of “smooth motion” to the destination.

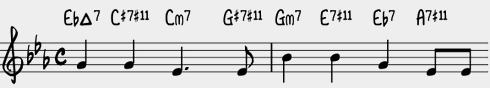

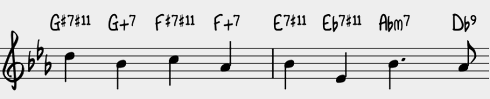

In the first two bars, I’ve found that I like using dominant chords coming from a half-step above:

The #11 of each approach, in particular, becomes the 5 of the final chord

which gives a solid feeling of tension and resolution.

Chords are only as good as their voicings — and since this is a ballad and we’re looking for “juice”, why not throw in as many color tones as our fingers can handle? Here are some suggested piano voicings for these changes:

Most of these voicings have the left-hand playing the root and 7, though root

and 3 or 5 aren’t uncommon, either. I particularly like the E7#11 chord

voicing, which in the right hand has just about every color tone that makes

sense to throw in there, including a #11 and b13.

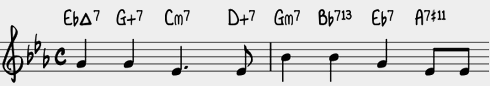

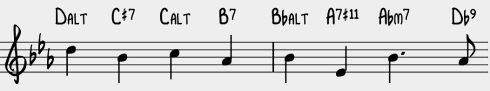

When I first met them, I found chromatic approaches to be both beautiful and vaguely mysterious. But with time I learned that they’re actually simple tools. Since we have to play the first two bars of the tune a few times, why not choose tritone substitutions for each of our chromatic approaches above? This gives us the following progression:

Wait a second — that looks familiar! Yep, chromatic approaches are simply

tritone substitutions for V7 chords that lead to the next chord. In this case,

for example, G+7 - Cm7 is simply a minor V7 - I progression, which we repeat

a few times more. If even this isn’t enough juice, it’s of course possible to

insert the missing II chords before the minor V7 - I changes… but you’ll

have to work out a different rhythm to make it feel sensible.

Here are some piano voicings I like for the tritone run through these bars:

The D+7 chord is worth looking at more carefully. First of all, the melody

note (a low Eb) gets raised an entire octave so that it fits. This allows us

to run a little melody, not part of the original piece, through the next bar and

onward.

The other interesting aspect of the D+7 voicing is that it places the 3

and the 7 in the left hand, allowing the right hand to play both the #9

and the b13 color tones. It’s a very rich voicing which I stole from McCoy

Tyner’s performance of Search For Peace on his album

The Real McCoy.

Angels Dining At The Ritz

Inserting new chords between chords that were already there is all well and good, but for this section we’re looking for something that truly dismantles the original harmony of the piece. The Manhattan Transfer won a Grammy for their recording of Nightingale, I think in no small part because they twisted the harmony in this passage until it was unrecognizable.

Let’s start by using the Abm7 as our “destination” chord. Whatever we decide

to do, we’ll be sure to treat this chord as our target. This makes some sense

given how the piece sounds — the Abm7 is an important point of resolution

that we don’t want to lose.

Another advantage of choosing a destination is that we can work backwards from

it. So, assuming we wanted a new and interesting chord on every melody note of

the passage, what would the chord directly before our target Abm7 be?

There are plenty of options, of course, but let’s choose a simple one and see

what happens. We’ll use a

secondary dominant

— a “dominant of the dominant” — to get going. (Readers whose eyes haven’t yet

glazed over may object that Abm7 is a minor, not a dominant — and this is

true, but it turns out the chord sounds well as a dominant, too, and taking a

secondary dominant to a minor chord is not unheard-of in these cases.)

So: the chord we choose for right before our destination will be an Eb7#11.

The melody fits nicely here — it’s the root of the chord!

What comes before the Eb7#11? We’ve got a Bb melody note to contend with.

Why not make it become an interesting color of the chord — say, a #11?

Actually, that turns out great, because then we’ll have an E7#11 chord here —

a chromatic approach to our chosen Eb7#11.

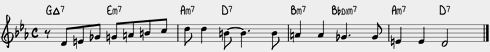

Let’s work our way back in this fashion, using secondary dominants and chromatic approaches until we reach the first note of the first bar. Here’s what we arrive at:

We’ll need to make sure it makes sense. Theory shows us that the each of the melody notes is a reasonable — even interesting — color of the chord we’ve chosen. But what does some good hard listening tell us?

Let’s choose some meaty voicings for these changes and try it out:

Very nice. There is a lot of motion in these voicings, but all of it is smooth to the ear. The original 1940’s “happy” of the passage has been replaced with something substantially more subtle and complex.

Of course, we’ll have to play these two bars a few times. So what can we do to mix it up the next time around? Since all of our chords are dominants, one simple approach is to choose tritone substitutions for each of them:

Once again, the melody notes are sensible with respect to the chosen chord. And

another interpretation of our new harmonization suddenly appears: we’re just

chaining chromatic approaches for as long as it takes to to reach the Abm7.

For performance on the piano, we can keep our right hand voicings and just alter the left hand to get the desired sound:

Again, colorful and interesting without being too “far out” there. What if we have to repeat this passage more than twice? Easy: we can simply mix tritone-subsituted and regular chords to get yet more interesting variations.

The Moon That Lingered

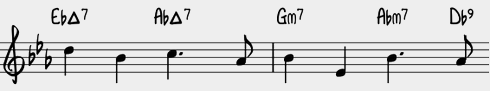

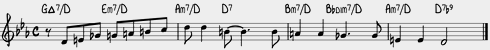

The bridge of the original Nightingale is very happy, indeed — listen to Vera Lynn’s recording above, for example. This is a bit surprising given the number of minor chords along the way, but it’s all in the feel and motion of the melody:

After the complex changes of the “A” section, perhaps it’s a good idea to hew

closer to the bridge’s original form. So what can we do to add interest without

completely altering the landscape? A quick scan through the bridge’s changes

reveals that D is a meaningful note in all of the chords. Why not use it as a

Pedal Tone

throughout these four bars?

This is simple enough to play — in fact, we can just hold down an octave in our left hand and put all of the color and interest into our right. The movement of the melody also gives us an opportunity to use some fun contrary motion to add interest to our performance.

All Together, Now

So, what does it sound like when we tie it all together? I recorded myself playing with these changes so that you can check it out: Yours Truly Performing “Nightingale”

Of course, if you want to improvise with these changes yourself, you’ll need a lead sheet. Here’s one that I worked up in a trial copy of Sibelius First last night: Lead Sheet For Reharmonized “Nightingale”

If lead sheets aren’t your thing or you’re just not feeling the improv on this piece, here is a fully worked-out score that is a somewhat simplified version of my recording above: Example Piano Score For “Nightingale”

Special thanks go to Bogey Vujkov, who originally showed me how to reharmonize the “Angels Dancing” section of the piece. He apparently learned it, in turn, from his teacher Billy Taylor. It’s funny how good ideas spread in the jazz world!